The Christoforo Syndrome

Kelly Lynch // January 9, 2012

By now, the name “Ocean Marketing” is probably very familiar to those of us in the PR world. It’s also in all likelihood synonymous with “disaster”. The email exchange began as a simple, polite request from a customer to Ocean Marketing and escalated (or devolved) into what is being called the last spectacular PR flop of the year. PR Daily very aptly called it a tale of “brand suicide”. This particular spectacle has also proven that when you flash your arrogance at the internet, you had better be prepared for the ramifications.

Paul Christoforo, president of Ocean Marketing, found out quickly enough that any power he thought he had could in one night be engulfed entirely by a harsh tide of binary.

Christoforo was contracted by N-Control to head customer relations for the Avenger PlayStation 3 Controller. The controller was originally created by Dave Kotkin, N-Control founder, who explained the controller had been designed for a student who had a physical disability. The controller allows gamers to press the top facing buttons without lifting their thumb from the analog stick. Christoforo did a poor job of upholding the integrity of the product, not only through an absolute lack of information for customers, but also through his blatantly disrespectful behaviour.

If you want more detailed proof, you can read the emails for yourself.

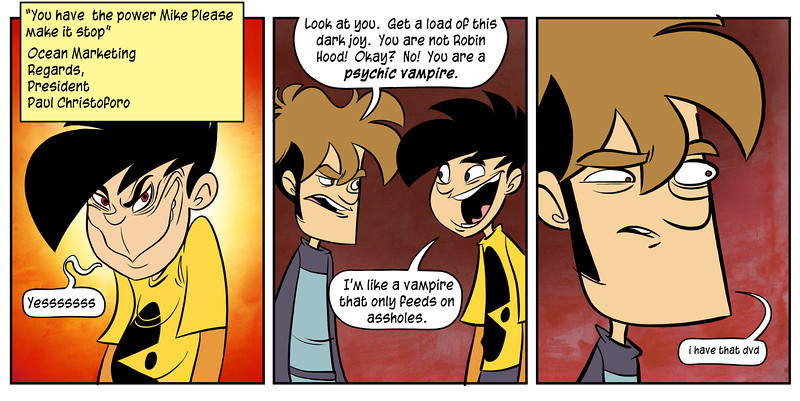

The customer known as “Dave” received several offensive emails from Christoforo and, fed-up, sent a transcript of the correspondence to one of the creators of the webcomic Penny Arcade, Mike Krahulik. Krahulik, defending the “little guy”, took it upon himself to address the issue.

Thus began the tale of Dave and Goliath.

After Krahulik posted the email transcripts on the Penny Arcade blog, it was all over for the self-proclaimed PR giant. Decimated on Twitter, he was disowned by many of the organizations he name-dropped so confidently. More, Ocean Marketing was bombarded by hundreds of angry customers suffering the same plight as Dave, or those simply seeking internet justice. Christoforo even became an overnight meme sensation.

All chuckles and internet justice aside, the sad thing about this entire ordeal is that it goes beyond the mere self-destruction of a PR consultant. Christoforo only felt it necessary to apologize after first thoroughly offending Dave and Krahulik, and then threatening Krahulik with legal action–and in the process, damaging N-Control’s reputation. Krahulik quite eloquently summed it up when he stated in his blog “I think there is a big difference between being sorry and being sorry you got caught”. What does it say about public relations as a profession when people like Paul Christoforo are somehow allowed to become successful?

“Public relations as an emerging profession continues to struggle toward defining its identity and its contribution to the bottom line. The challenge is to operationalize intangible public relations processes and to quantify the outcomes of relationship-building. One such outcome that has been shown to be influenced by an organization’s public relations activities is its reputation (Kim, 2001)” (Kiousis, 2007).

Christoforo is just another in a long line of incidents involving public relations that have given the profession a bad name. He was, and most likely still is, ill-informed, seemingly unaware of communication theory and best practice, arrogant, unethical, and technically incompetent. The Ocean Marketing scandal has shown that public relations plays a very important role in the proper management of an organization’s reputation; more, it has helped make clear the fragility of the reputation of PR professionals overall.

As a young profession, public relations is still defining itself–there will of course be some blunders during this process, made only more evident because the work practitioners do is so closely tied to mass media. Public relations also lives and dies by public opinion, and the power of the public voice is great. When public relations is not trusted (or trustworthy) to begin with in the eyes of the general public and “according to public opinion”, how can the profession expect to grow, to become better?

Though Christoforo did eventually get his “comeuppance” as it were, it does not undo the damage. The emails made it evident, as Mike Krahulik said, that the president of Ocean Marketing was sorry he was caught, and that he would not be if his misdeeds hadn’t been publicized.

The unfortunate reality is that corporate North America is broad, but as a result it is also shallow. There is no doubt that there are hundreds, even thousands of PR professionals exactly like Paul Christoforo that exist worldwide, covered in a capitalistic security blanket. Fooled by confidence, fuelled by impatience in a fast-paced world, organizations allow the Christoforo’s of the world to sidle in and smear the reputation many public relations practitioners are attempting to build through ethical practice.

How does the public relations profession be proactive about this, our own internal crisis? Education? Regulation? In the big, “bad” world owned and operated by big business, how do practitioners maintain ethical practice? How do we prevent the “Christoforo Syndrome”?

The answers aren’t easy, but neither are they unachievable, at least to some extent. Practitioners must continue to communicate together as individual professionals, as academics, and in an organizational capacity. It is possible to find methods of best practice that diminish the probability of incidents and individuals like Paul Christoforo from occurring in the field of public relations. The Ocean Marketing scandal should only remind practitioners they need to respect their audiences, be aware of messaging, and to conduct themselves in a just, ethical, and dignified manner in the face of conflict or crises.

Kiousis, S., Popescu, C., & Mitrook, M. (2007). Understanding influence on corporate reputation: An examination of public relations efforts, media coverage, public opinion, and financial performance from an agenda-building and agenda-setting perspective. Journal Of Public Relations Research, 19(2), 147-165. doi:10.1080/10627260701290661