Alison DeLory

I was at the front of the second-year persuasive writing class talking about Aristotle’s modes of persuasion when I stopped and paused. I was about to say that ethos — the credibility of the speaker or writer — was an essential component of persuasion when doubt set in. “Ethos…” I continued slowly, “… tells us that when thought leaders and experts deliver messages they have more persuasive power.”

In public relations practice this traces back to Edward Bernays. He famously (if dubiously) enlisted medical professionals to help him study and deliver the message, on behalf of a pork producer he was representing in the 1920s, that bacon and eggs was the quintessential American breakfast. Time and time again since then public relations professionals have commissioned studies and consulted with experts in wide-ranging industries to endorse or communicate their messages.

But is ethos still valued, I asked myself, in an era when we are regularly told that a privileged elite is exploiting common people? When knowledge and skills, even for the top job in a country, are optional at best? When people boast of their lack of expertise?

Gulp.

My existential crisis was growing and nobody had time for that.

Stick to the lesson plan…sort of

My students looked at me expectantly with patient faces. I’m not an instructor who likes to wing it. I come in with my talking points considered in advance. But I also have to remain flexible and open to what happens in the moment, and stay humble enough to see the cracks in my lesson plans.

This semester, in addition to teaching persuasive writing at the Mount, I’m also teaching advanced media literacy at NSCC. I’m armed with textbooks, academic readings, and current examples of how theories like Aristotle’s are successfully put into practice. Yet lately I see many other examples that contradict much of what I teach. Not only is expertise condemned as elitist, communications advisors and press secretaries tell lies as often as truths, and the media — that essential fourth estate intended to hold power to account — are cast as the enemy of the people.

Three strategies:

After a few seconds contemplation I arrived at three conclusions:

- We live in confusing times in public relations, but rather throw our hands up, we need to question and challenge bad practice when we see it, while fulfilling our own professional obligations through leading by example.

- We need to keep ethical standards in mind always, and stand with the CPRS who has called for a renewed focus on ethical public relations.

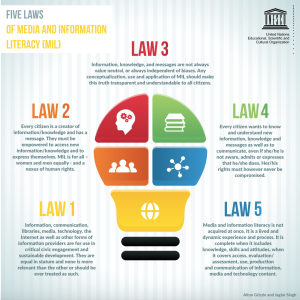

- We need media and information literacy more than ever both as informed citizens and to understand our responsibilities as professional communicators. Even UNESCO has recently drafted Five laws for media and information literacy and created a nifty infographic recognizing the urgency of this need (see below).

As public relations instructors and students, it’s always essential to adapt but to do so strategically. If Aristotle’s teachings have held for over 2,000 years, now is not the time to disregard them because the last three months have been weird. Let’s evolve not devolve, and let’s do it together as lifelong learners. I think Aristotle himself would approve.

Five Laws of Media and Information Literacy, click to enlarge.

Alison DeLory, BAA (journalism), BPR, MPR, is a part-time instructor in the Department of Communication Studies at the Mount.